If you’re reading this, you’re one of the 40% of people in the world with access to the Internet. Humanitarian groups, online businesses, and tech loving individuals are all vying to bring the Internet to the 60% currently offline.

But meanwhile, a conversation about the future of the internet is well underway, and laws surrounding how the Internet can be used might be in place before half of the world even has access to it.

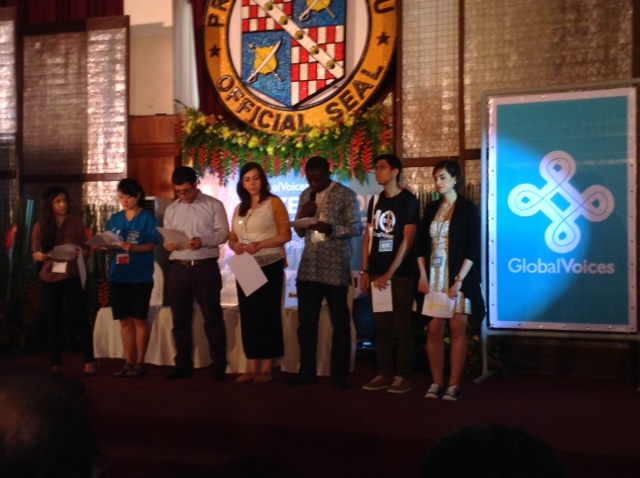

This January 22-25, the international citizen media network Global Voices convened in our beloved Cebu City, Philippines for their 2015 Summit. Over 100 bloggers, activists, journalists, and tech geeks from 60 countries led talks, panels, and workshops about internet freedom, citizen reporting, trolling, and more. They discussed what activism and revolutions look like at a time when everything is online: our opinions, our work, our personal pictures, our home addresses. Over the weekend (Jan 24 & 25), the Summit opened to the public and total attendance topped 300 people.

A panel on Internet Magna Cartas struck close to “home” for me. Filipino activist Mong Palatino spoke about the Philippines’ Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012, the concerns netizens (online citizen activists) had about the bill, and the bill they proposed in response: the Magna Carta for Philippine Internet Freedom. This topic struck me because last year I worked for International Justice Mission to combat child-trafficking in the Philippines. Online child sexual exploitation is a fast growing industry, with the government reporting that 71% of cybercrime cases handled by the police and investigative bureaus in the Philippines are related to online child abuse or the extortion of money using online sexual abuse. So laws that crack down on the cybercriminals exploiting children have been celebrated by those involved in this battle.

But although protecting children is a high priority for any human rights activist, those who have seen the disturbing aftermath of cyber-regulation firsthand have excellent reasons for being concerned about internet security laws like the Philippines’. In Bangladesh, blogging became a health hazard in 2013 after a blogger was killed for anti-Islamic sentiment expressed online. Soon after, eight blog operators blacked out their websites. Since at least 2010, Indonesia has moved to block all pornographic websites as enforcement of a 2008 anti-pornography bill. But critics claim that among the million-plus websites included in the government block are websites about sex-education, LGBT rights, and sexual violence.

And while Europe and the United States engage in internal debates over net-neutrality and the right to be forgotten, their behavior and products are influencing human rights battles internationally. Ethiopia has been using European-bred software to track its citizens across at least 25 countries, including Ethiopians living in the US and the UK.

Renata Avila of WebWeWant, a campaign for a people-driven future of the web, said at Global Voices Summit 2015, “The Internet changed everything, but it also changed nothing. It changed everything about how we live, interact, and access information, but it should have changed nothing about human rights.” According to Avila, appropriate conversations about Internet freedom and cyber security should start within the framework of the International Bill of Human Rights. From there, individuals should be able to decide what kind of internet they want, including what level of censorship and government-driven security.

But while 60% of the world remains offline, decisions are being made. China held a World Internet Conference where its leaders promoted their view of how the Internet should be run. According to Business Insider, Lu Wei, China’s Internet czar and director of the Cyberspace Administration of China, said at the opening ceremony, “Cyberspace should also be free and open, with rules to follow and always following the rule of law.” Brazil’s citizens championed the Civil Law Marco Internet to guarantee equal access to the nation’s internet and protect the privacy of users.

I don’t know what the right balance is between protecting personal privacy and protecting children from online exploitation. There are a lot of difficult questions being asked and more that need to be asked.

But what I do know is: if you want to influence these decisions, for your country or internationally, the time to act is now.